Why is it relevant?

Engaging relevant stakeholders is key to running successful Citizen Observatories. A fundamental part of stakeholder engagement is identifying key stakeholders and the larger context in which a Citizen Observatory is (being) embedded in order to know who, why, how and when to engage.

How can this be done?

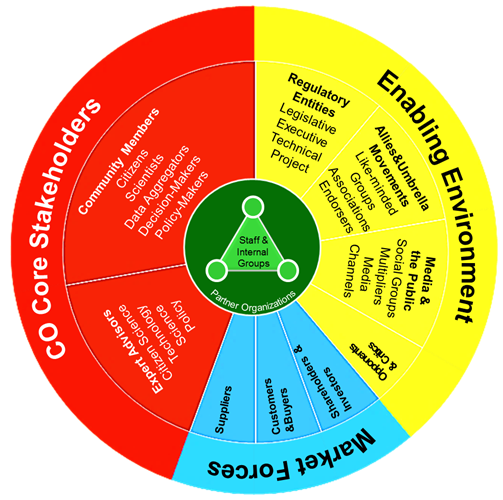

Deciding which stakeholders are relevant for a Citizen Observatory can be quite complex, especially given that Citizen Observatories are typically linked to (local) issues and policy. Moreover, stakeholders from the same category, e.g. citizens, can play distinctly different roles in an observatory, e.g. as initiator, core community member or observer only and need to be engaged accordingly.

It is therefore important to carefully map the context of the issue and the key stakeholders in order to navigate these. Simple context and stakeholder mapping is a generic approach that is being used in many project-related contexts. It can help to identify and specify the social, economic, environmental and political setting of the observatory as well as the roles, relationships and agendas of different actors.

Useful Resources

PROJECT REPORTS: These Ground Truth 2.0 reports explain the context and stakeholder mapping approach, including the adapted PESTEL. They present the findings of the baseline context and stakeholder mapping per case in Africa and Europe as well as the subsequent updated analysis one year into the project.

SCIENTIFIC PAPERS: The Ground Truth 2.0 project produced this conceptual framework for context, process and impact analysis and applied it in two of the Ground Truth 2.0 Citizen Observatories, one in the Netherlands and one in Kenya to create a baseline.

CoP: The WeObserve Co-design & Engage Community of Practice brings together practitioners of Citizen Observatories and citizen science to share and learn different ways of engaging stakeholders in Citizen Observatories.

You may also be interested in:

I want to engage stakeholders…

This work by parties of the WeObserve consortium is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ![]()