Why is it relevant?

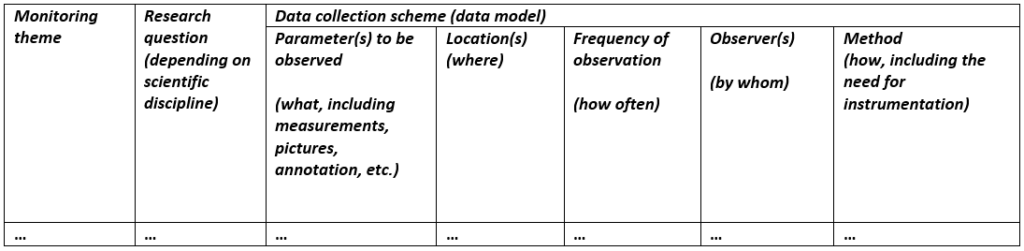

Deciding what kind of data the members of your Citizen Observatory should collect depends on the issue that your Citizen Observatory wants to address and what data and knowledge is still needed. Moreover, this decision needs to be informed by relevant scientific expertise in order to generate valid and reliable data and results.

How can this be done?

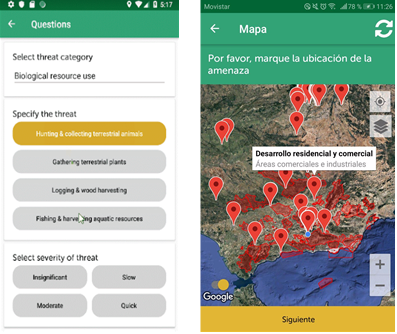

Citizen Observatories are based on citizens observing specific aspects of the environment, sometimes using equipment. For this kind of data, the user’s identification, the time and place of the observation, the value of the observation and some supporting material like images, audio recordings or videos for validation purposes are usually collected.

Observations can be as simple as registering a temperature or as complex as taking a lot of measurements as in the RiuNet project, where citizens conduct a complete scientific analysis of several organic and inorganic parameters indicating river water quality. These types of observational data include biodiversity observations, environmental monitoring, meteorological observations, hydrological measurements, land cover mapping and more.

In some cases there is no data collection by validation or interpretation of scientific data, and no contribution to pattern recognition or image analysis. An example is citizens helping scientists to map the ocean trajectories of marine microbes within a simulated web environment (the Adrift project). Another is the annotation of satellite observations or other pictures with what humans can recognise (such as identifying wildlife captured by motion-triggered camera traps). In particular, Zooniverse is probably the most well-known platform for hosting projects where citizens can participate from their homes, just by using a computer and their time.

Example from the Citizen Observatory of Water in the Alto Adriatico Region

A challenge for water management is the reduction of risk related to extreme events such as floods. Flood management requires the timely provision of early-warning information, particularly in densely populated urban areas. This information depends on reliable water level predictions, created through hydrological and hydraulic models. Yet the performance of these models is often uncertain due to the lack of sufficient observational data. In the Brenta-Bacchiglione catchment area, AAWA has chosen to use the Citizen Observatory on Water to collect complementary sources of hydrological monitoring data to obtain a more spatially distributed coverage, using dedicated apps, easy-to-use physical sensors and other monitoring technologies, linked to a dedicated platform. The crowdsourced water level observations are assimilated into a flood forecasting system: into the hydrological model by means of rating curves assessed for the specific river location, as well as directly into the hydraulic model. This improves the flood forecasting accuracy by integrating physical and social sensors distributed within the river basin, ensuring high model performance (see https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-839-2017; https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-391-2018). Other environmental variables, such as the vegetative state of the embankments and the river bed, are important for the calibration of the hydraulic models, and for evaluating the hydraulic roughness along the river. On the other hand, knowing the exact location of the flooded areas during a flood event and the relative water height can be useful both post-event to evaluate and improve the reliability of the model, and during the event to plan civil protection operations. The collection of these data in the Brenta-Bacchiglione catchment area is also entrusted to the Citizen Observatory, being easily identifiable through the use of a dedicated app.

Useful Resources

BOOK: The AfriAlliance Data Collection Handbook is a practical manual focusing on the development sector and the collection of data. It covers the main elements to consider when designing and implementing a data collection project.

BOOK CHAPTER: The chapter “Design and development of geographic citizen science: technological perspectives and considerations”, in the book ‘Geographic Citizen Science Design: No one left behind’ highlights the various impact of information technology on the aims, goals and missions of citizen science and Citizen Observatories.

You may also be interested in:

I want to work with data…

I want to know what data and knowledge we need…

This work by parties of the WeObserve consortium is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ![]()