Why is it relevant?

Your Citizen Observatory is fully up and running and you are collecting lots of data. Now you need to translate these data into meaningful information. You might also want to use this information to trigger behavioural change or feed these added value insights into current policies and decision-making.

How can this be done?

Turning data and information into knowledge and insights requires analysis of the data. It goes beyond data visualisation and interpretation (more about that here), since it implies performing more complex operations and using the collected data.

This step needs to be informed by scientific expertise, depending on which environmental issue you are focusing on, to make the analysis reliable. For this reason, it is important to make sure you don’t tackle this process without the support of relevant scientists, who will guide the data analysis and propose suitable methodologies for generating relevant and trustworthy conclusions (more on how to engage key stakeholders here).

Data analysis can be done deductively or inductively. Deductive data analysis means answering the research question using existing scientific concepts, theories and methods. Inductive data analysis starts with data broadly related to a topic (not with research questions) and looks for patterns in the data to arrive at insights and explanations for those patterns.

Useful Resources

TOOLS: Google Maps and Google Charts are easy and inexpensive tools to help Citizen Observatories do some simple EDA.

TOOL: QGIS is a free and open-source Geographic Information System in which users can access various types of spatial analysis tools for working with their data.

BOOK: Python for data analysis is a useful open-source book on the Python programming language, which can be used to analyse data.

DATA ANALYSIS TOOL: Building on python for data processing, the use of Pandas is one of the most popular choices due to its simplicity and complete ecosystem.

TOOL: The R programming language provides very powerful data analysis tools.

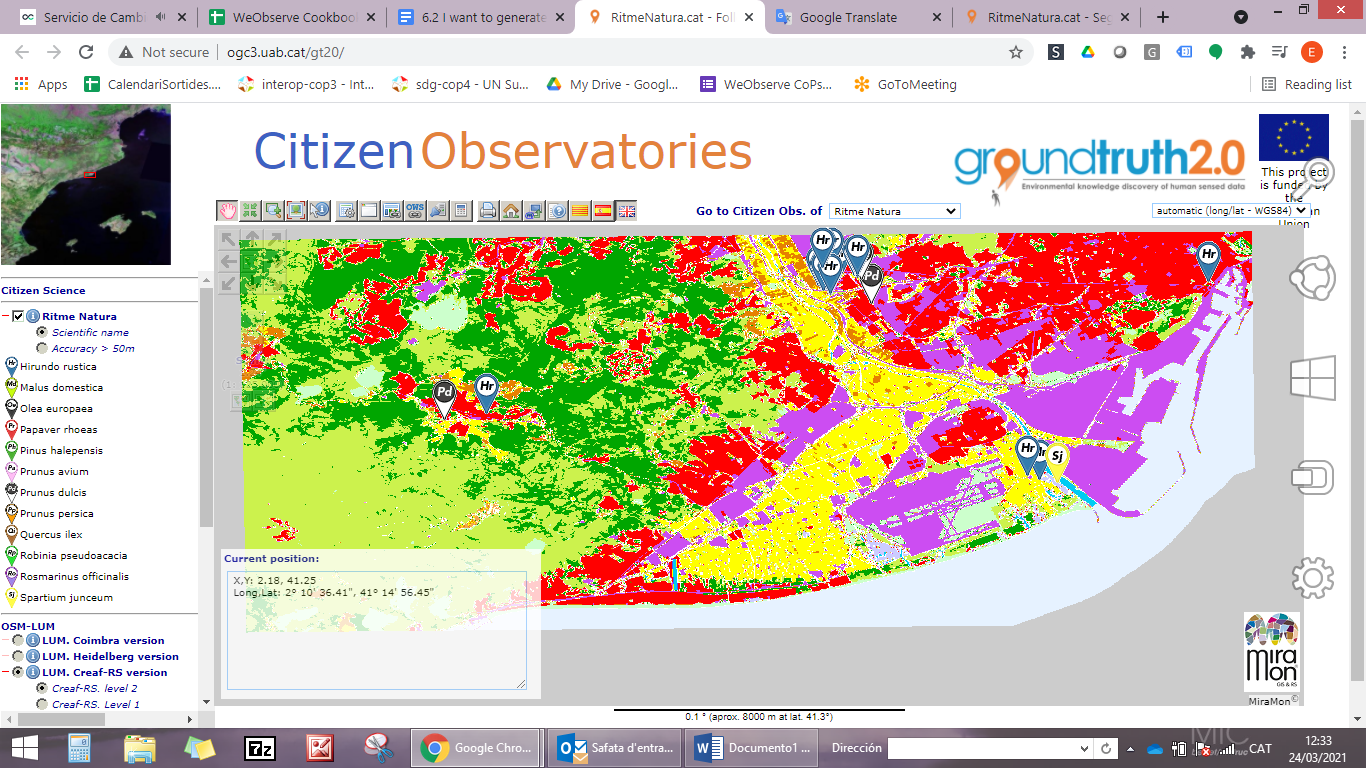

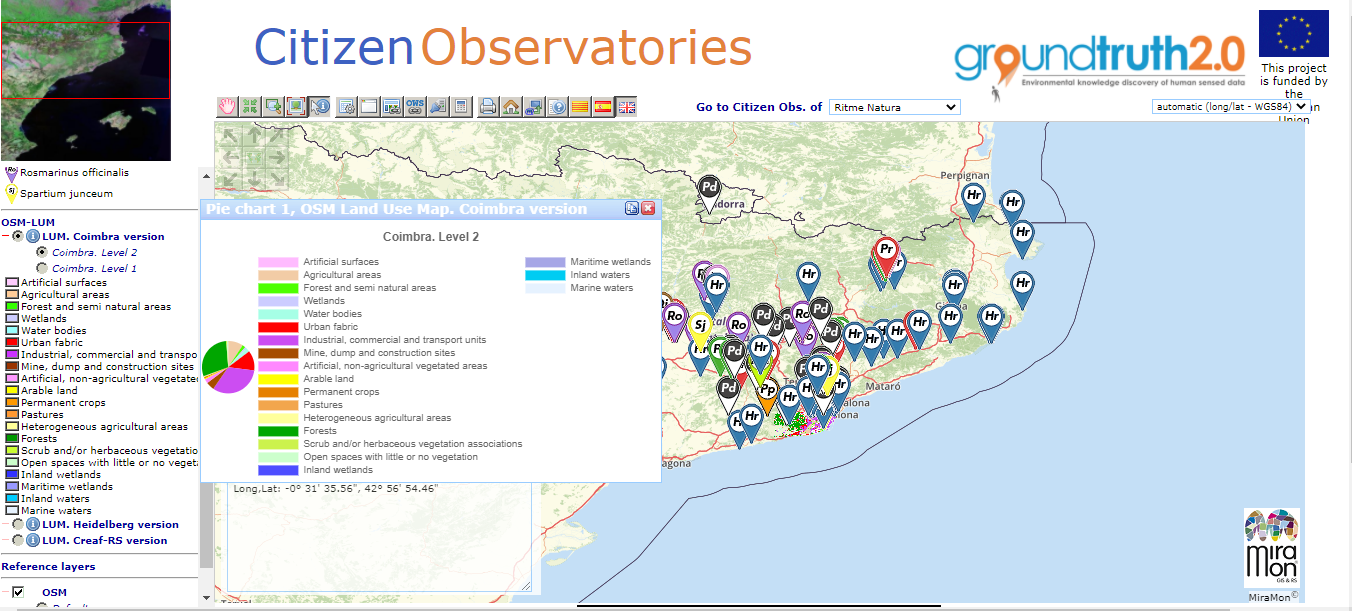

SCIENTIFIC PAPER: The paper “Assess citizen science based land cover maps with remote sensing products: the Ground Truth 2.0 data quality tool” provides information about a tool which shows and compares maps as part of the MiraMon Map Browser.

VIDEO: “How We Did It: Analysing Data” describes data analysis approaches from the different Citizen Observatories in the WeObserve project.

TOOL: The MiraMon Map Browser is a tool for creating visualisations and analysing data that is provided as open-source code.

TOOL: PYBOSSA is a crowdsourcing framework to analyse or enrich data that can’t be processed by machines alone.

You may also be interested in:

I want to generate insights & results from our data & knowledge…

This work by parties of the WeObserve consortium is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ![]()