Why is it relevant?

It is important that you can deliver a clear message to stakeholders and/or policy-makers in order to affect the changes that your Citizen Observatory suggests. Creating engaging visualisations is one effective way to do that.

How can this be done?

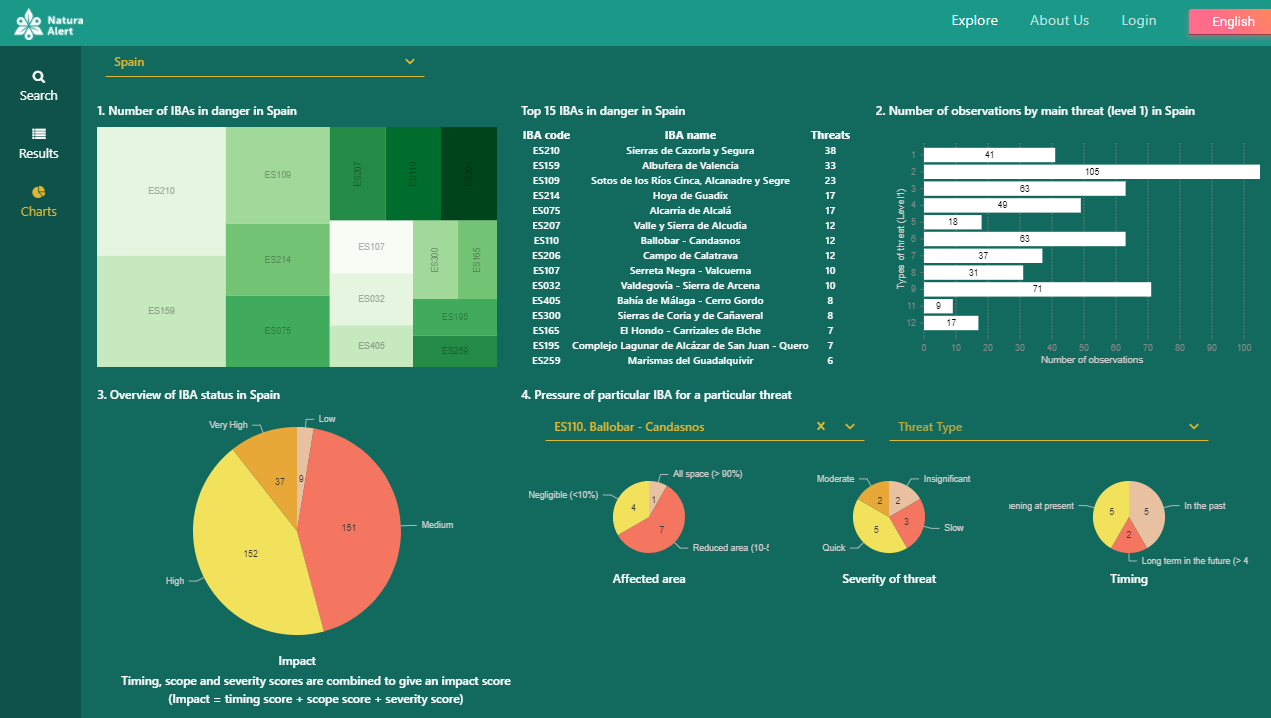

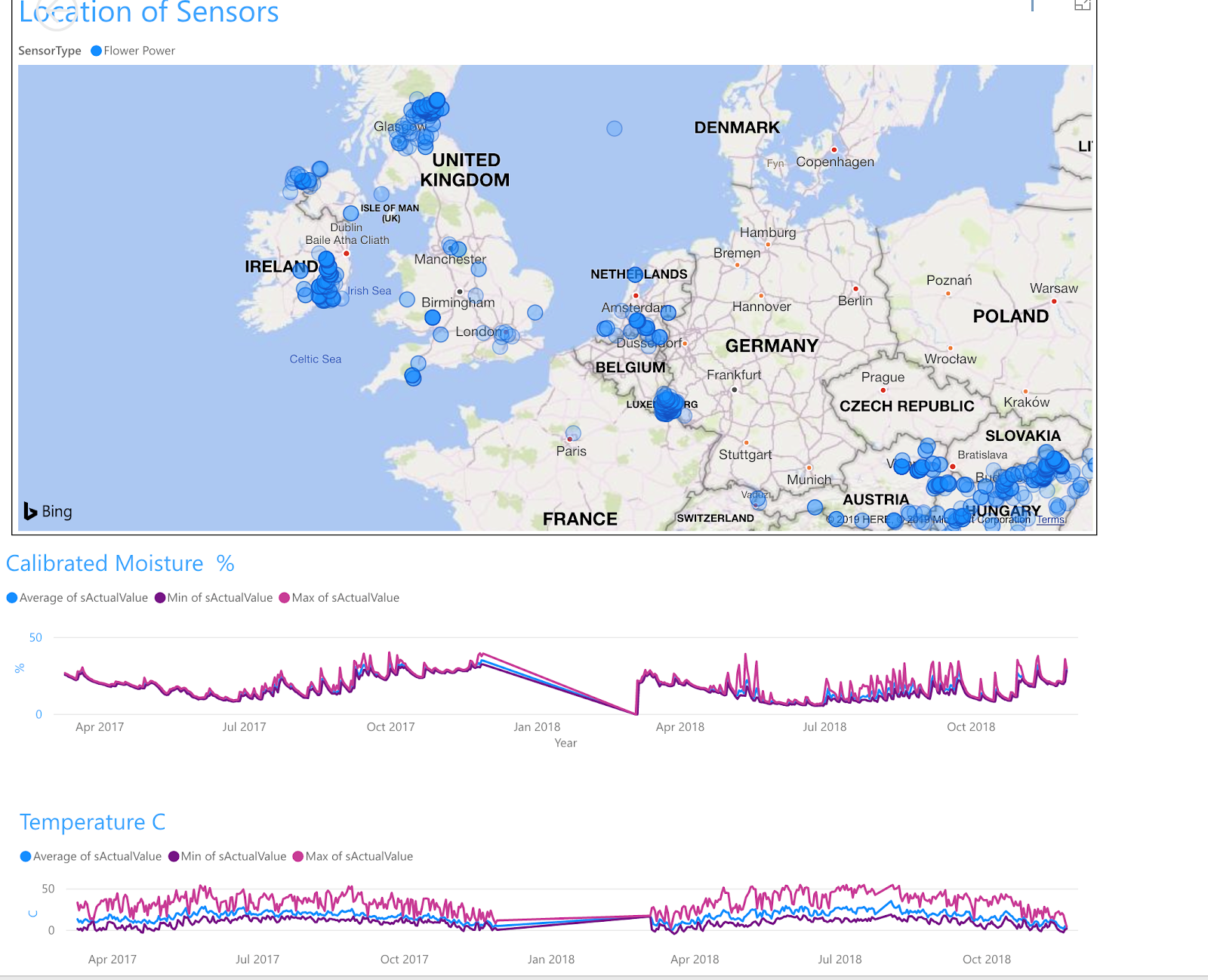

“A picture is worth a thousand words.” This old saying also applies to Citizen Observatories, where data visualisation can help you and your participants to explore and understand data and to communicate results quickly and in an engaging way. Nevertheless, when it comes to extracting meaningful information from data and interpreting the data, scientific knowledge may be required so that the interpretation is accurate and meaningful. Data visualisations, besides communicating results, can also be used as a tool for data interpretation by helping to detect gaps, errors or inconsistencies in your data sets.

Useful Resources

WeObserve MOOC, enrollment is now open: The online course Citizen Science Projects: How to make a difference on FutureLearn addresses data analysis and visualisation in depth, including many examples, discussion of biases in data visualisation, and data sets for you to experiment with.

VIDEO: “How we did it: Visualising Data” provides more examples of data visualisations from four Citizen Observatory projects.

TOOL: WeObserve Toolkit for data quality and visualisation is a selection of tools that can help you with all aspects of citizen-generated data management, including validation, analysis, quality assurance and visualisation.

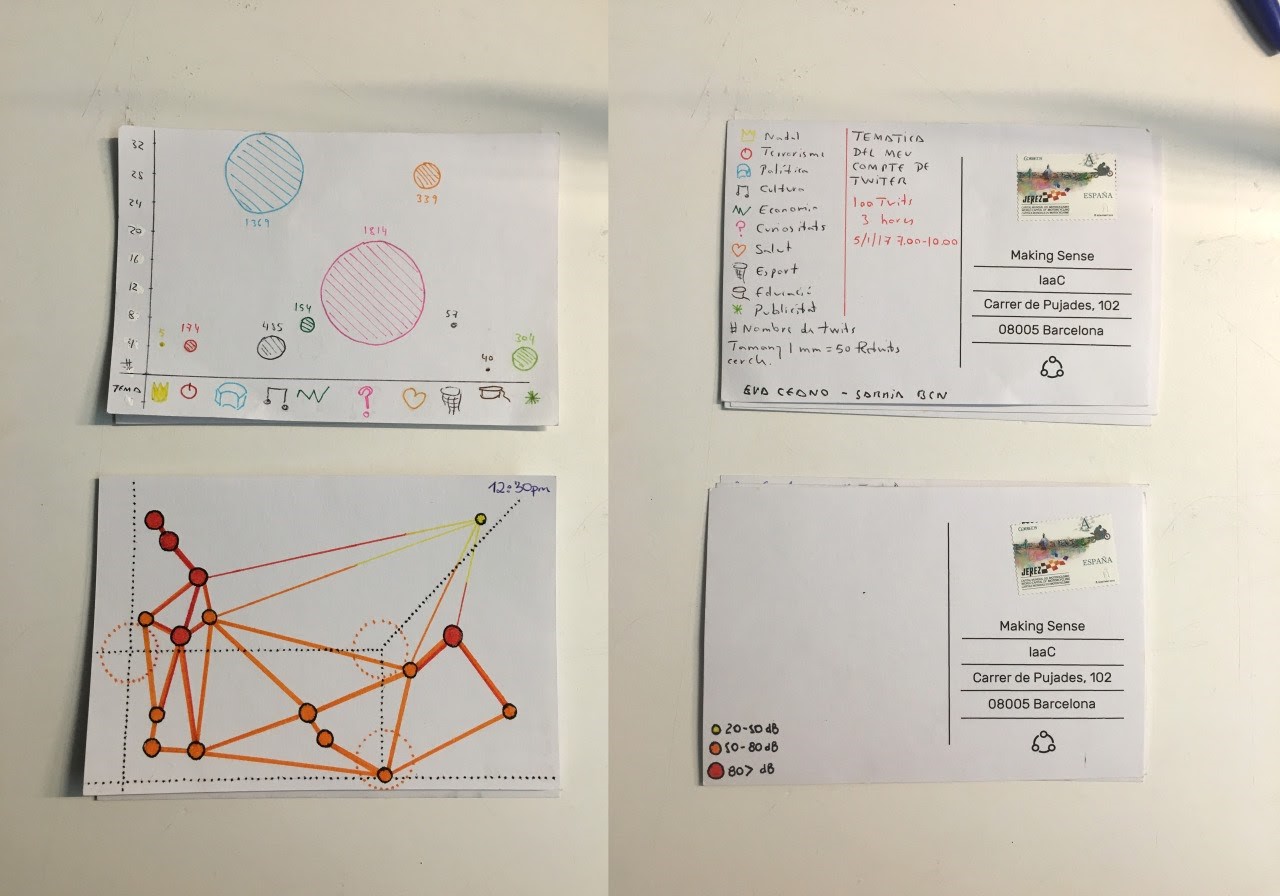

TOOL: The Data Postcard tool is designed for community members and citizen science practitioners wanting to share the data they collect. It is a creative way to visualise and share data from a citizen science project.

Data visualisation applications:

- Matplotlib: For those of you with programming experience, Matplotlib is a popular choice for data visualisation and can be easily integrated into Jupyter notebooks.

- Leaflet: Leaflet is an open-source JavaScript library for mobile-friendly interactive maps. It works efficiently across all major desktop and mobile platforms, can be extended with a variety of plugins, and is well documented.

- Other free tools: Grafana, Rawgraphs, and Apache Superset

You may also be interested in:

I want to generate insights & results from our data & knowledge…

I want to achieve impact with Citizen Observatory results…

…by communicating the Citizen Observatory results effectively

This work by parties of the WeObserve consortium is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ![]()

This page partially draws upon the MOOC Citizen Science Projects: How to make a difference, though the focus was shifted from citizen science projects to Citizen Observatories.